Apply to a foreign university with confidence

- Properly fulfilled documents

- Perfect motivation letter

- Support from a personal mentor

- Offers from several universities

Article score: 4.04 out of 5 (27 reviews)

A motivation letter is the most important document in an applicant's application. How to write it? Look for examples, ideas, recommendations, as well as common mistakes in the article.

Free consultation

Admission committees are simply piled with documents of honor students, competition champions and other remarkable students. Everyone writes how good he is and how eager he is to study in this particular institution. But how to choose among thousands of profiles just a few dozen of those who are really worthy to study there?

In this article, we look at the world of admission through the eyes of those who make this decision. And we will tell you in detail how to write the one motivation letter (also called the statement of purpose) that will break through this insurmountable barrier.

| Specialty | Degree | University | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medicine (Neurobiology) | Bachelor’s | Brown University | Download |

| Engineering | Bachelor’s | Caltech | Download |

| Biology | Bachelor’s | Cornell University | Download |

| Telecommunication technologies | Master’s | MIT | Download |

| Engineering | Master’s | Harvard University | Download |

| Law | Master’s | London School of Economics | Download |

| Medicine | Master’s | University of Oxford | Download |

| Management | MBA | Harvard Business School | Download |

"It is possible to redeem yourself (in certain cases) or to kill your chances of admission with the personal statement." — Ruth Miller, Former Director of Graduate Admissions to Princeton University.

A motivation letter through the eyes of the heads of faculties and the admission committee is the most important document in the application of the student. The rest of the papers will not be able to tell much about your personality unlike a motivation letter. In a few hundred words you need to fit your interests and achievements along with your hopes and dreams. Yes, it’s not easy... But it’s worth doing, because it is right here where you have a chance to turn the tides and show your uniqueness, even with sub-par language skills and not so outstanding achievements.

Let's try to figure out how to write a perfect motivation letter. After all, your future depends on it.

The answer is quite obvious. The selection committee wants to find out who is hiding behind a mountain of similar documents that end up on their hands.

Motivation letter should create a vivid idea of personality. What describes you as a person? Ambition? Sense of humor? Self-awareness? Imagination? Sociability? This is what you have to find out during the preparation of the motivation letter.

Here are some citations of the representatives of leading American universities confirming this idea:

An interesting short story written in a vibrant, dynamic language is the main requirement that experts insist on. Through a motivation letter, professors want to find out what goals future students are pursuing, what they want to achieve in life, how they can be useful to their university and society as a whole. The main thing is not to overdo it: avoid wordiness, deceit and floridness in the text. No need to send a letter that is bizarre and hard to follow — you need to be yourself, but try to express your thoughts vividly, since you can not use gestures and facial expressions.

More precise recommendations were made by Vince Gotera, professor of English Language and Literature, University of Northern Iowa. In his opinion, the motivation letter should show the applicant as a person:

This is a lot of stuff to fit in a few hundred words, so it is worthwhile to approach each of the points sensibly. No need to describe them in the same order in which they are on the list of the university. Combine, move them, do everything to show yourself as an inventive person, and not a parrot following a line of Brazil nuts to crack.

Many students perceive recommendations for writing a motivation letter as unbreakable rules, dogmas, a universal template. It seems that if there are six bullet points, then every single one should be mentioned, although in reality all this may mean nothing for the admissions committee, and even for the student himself. Often, one achievement can dwarf all others.

A purely hypothetical example: there is a student, a physicist who destroys local competitions, in his spare time builds a time machine and compiles on C. But he read in our instructions that it is necessary to mention this and that, and wastes a whole paragraph of already limited page real estate in order to tell how he helped old ladies to cross the street. Of course, volunteering is a good experience, but does it say anything about a real passion for the profession? Words and sentences in a motivation letter are your "nonrenewable resources", which should be spent only on really significant information.

A real case: a student was applying for a computer science program. In his time he had already launched two startups and in his letter described his apps a little. Then he moved on to the painfully familiar and tired pattern about how he wanted to study and how much he was interested in the chosen field. I asked him to write some more about the difficulties in development and how he had overcome them. This information is not only directly related to the profession, but also demonstrates to the admissions committee that the applicant is able to think critically and has problem-solving skills. He very quickly came up with another half-a-page about how he had troubleshoot various bugs and implemented features. It was a vivid, interesting read and, most importantly, it demonstrated the genuine interest in the profession that could so easily be lost in a series of general statements and cookie-cutter phrases. At the same time, for some reason, he did not consider it to be necessary to write this in the first place, despite the fact that this exact thing matched the profile of his education.

The point of the whole story is that if you have a relevant shtick, then it should be the core of your motivation letter. There is no need to spend valuable space on often mundane and insignificant information in an attempt to tell about everything in the world just because the article says so. As Barbossa said in "The Pirates of the Caribbean": “The code is more what you'd call "guidelines" than actual rules”. There are general principles, tips, but the final result depends solely on you.

In general, most motivation essays can be divided into two categories — unstructured letters, and essays in the form of interviews (or short essay answers to specific questions). The latter are often written by the applicants of overseas MBA programs. In an unstructured essay, the candidate provides information about himself — his achievements, personal qualities, interests, experience, and future goals. Despite the name, in an unstructured essay it is also advisable to adhere to a specific structure, or format. For example:

Option 1: Yesterday — Today — Tomorrow

Option 2: I — You — We

Option 3: What — Why — For what purpose

Many universities (especially at the master's and doctoral levels) offer applicants specific, sometimes tricky, questions that involve stepping outside the template structure. Here are some of them:

What is interesting is the fact that, in general, any question presented here can fit seamlessly into a narrative of an unstructured motivation letter. But separately, they provide the student with more opportunities for an in-depth analysis and disclosure of the topic.

"If you are going to write a winning personal statement, you cannot do it in two or three hours; it requires a lot of thought." — Faye Deal, Director of Admission, Stanford Law School.

A good essay cannot be written at the snap of a finger. That is why many experts advise starting preparing a few weeks, or even months, before the deadline.

For convenience, let us divide the process into three stages: preparatory, main and final.

"What I would love to have people do in preparing their essays is to do a great deal of self-assessment and reflection on their lives and on what’s important to them because the most important thing to us is to get a very candid and real sense of the person." — Jill Fadule, Director of Admissions, Harvard Business School.

It is often difficult for people to start writing something personal about themselves that requires introspection. If you often face a fear of a blank slate, try the following tips[1]. Creative solutions will not take long.

Record all events that happen to you, be that new experiences or abilities. Never underestimate anything. You may think that a summer trip to Europe, a recently read book or your newly discovered talent as an artist is not so significant, but it is. The sooner you start doing this (several weeks, months), the better. At the same time, you should not immediately evaluate your experiences in terms of their usefulness. Keep this until the next stage.

Try creating an experimental sample of your essay. Imagine that you are taking a creative writing course, and your task is to write a couple of pages about an event from your life that has had a significant impact on you. This must be done so that after reading the essay in front of strangers, they feel as if they have known you for a very long time. It might feel like a rather stupid exercise, but as we heard from the statements of the members of the admission committee, they expect this approach from the applicant.

Before you start writing, it is advisable to brainstorm ideas. Try to answer questions about yourself, your goals and features, while outlining as many variations as possible. Then select those that will serve as your guidelines in the process of writing your essay. Be honest and remember that the answers often lie beneath the surface.

The same questions can be used to prepare for the interview. As in the letter of motivation, members of the selection committee will want to hear the information that you personally consider important or worth their attention. Having thought over the answers in advance, you definitely will not get confused during the conversation.

It is equally important when preparing a motivational letter to find someone who could share their perspective. If you could not immediately answer all the questions from the previous exercise or if you have doubts, seek help from professors, friends, colleagues, and just acquaintances whose opinion is valuable to you. You can send a small questionnaire by e-mail or ask to answer in a personal conversation.

Enrich your list with more specific questions, depending on who you ask. Tell them which university you are planning to enter. Give each person the opportunity to comprehensively and objectively evaluate your experience and abilities.

In the main section, we decided to provide some practical recommendations from the article How to Write a Great Statement of Purpose by the Professor of the University of Northern Iowa, Vince Gotera[2].

The Statement of Purpose required by grad schools is probably the hardest thing you will ever write. I would guess virtually all grad-school applicants, when they write their first draft of the statement of purpose, will get it wrong. Much of what you have learned about writing and also about how to present yourself will lead you astray. For example, here's an opening to a typical first draft:

"I am applying to the Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing at the University of Okoboji because I believe my writing will blossom at your program since it is a place where I will be challenged and I can hone my writing skills."

How's that? It's clear, it's direct, and it "strokes" the MFA program, right? Wrong. All of it is obvious and extraneous.The admissions committee knows you are applying to their MFA program because everyone in the stacks of applications they are reading is applying for the same thing. The admissions committee will also know that your writing will "blossom" there since they feel they have a strong program. Of course you will be challenged — all undergrads going on to a grad program will be challenged, no matter how well-prepared they think they are. And of course the new grad student will "hone [her] writing skills" — isn't that the main purpose of the MFA program?

Let's assume the required length of this particular program's statement of purpose is 300 words. Well, with this opening you will have used up 15% of your space saying virtually nothing. 15%!

In fact, not only is this opening paragraph obvious, extraneous, and space-stealing, it's boring! Imagine who's reading this and where: five professors "locked" in a room with 500 applications. Do you think this opening paragraph will command their attention? Will they read the rest of this statement of purpose with an open mind that this applicant is the kind of student they want? Will they remember this application later? You be the judge.

For a successful motivational essay, you need the so-called "hook". For example, one student of the master's program in library science made an excellent “hook”. It looked something like this:

"When I was eleven, my great-aunt Gretchen passed away and left me with something that changed my life: a library of 5,000 books. Some of my best days were spent arranging and reading her books. Since then, I have wanted to be a librarian."

Everything is clear, it's direct, it's 45 words, and, most important, it tells the admissions committee about Susan's almost life-long passion not just for books but for taking care of books. When the committee starts to discuss their "best picks," don't you think they'll remember her as "the young woman who had her own library"? Of course they will, because having had their own library when they were eleven would probably be a cherished fantasy for each of them!

"I am honored to apply for the Master of Library Science program at the University of Okoboji because as long as I can remember I have had a love affair with books. Since I was eleven I have known I wanted to be a librarian."

Surely the admissions committee will not remember this student among the other 500 applications they are wading through. Probably more than half of the applications, maybe a lot more than half, will open with something very similar. Many will say they "have had a love affair with books" — that phrase may sound passionate until you've read it a couple of hundred times.

A student named Jennifer wanted to get a master's degree in speech therapy. When asked why she chose this direction, Jennifer said she had taken a class in it for fun and really loved it. But during further discussion the girl remembered that her brother had problems with speech. This was a discovery to her. She had not entered the field with that connection in mind — at least not consciously. But there it was; Jennifer now had her hook.

You have the same task: to find this "hook", to understand why the choice fell on this particular direction, what benefit the applicant can bring with his work in the future, how this will affect him and the others. Find your own truth, and then choose a memorable way of expressing your thoughts.

Equally important for the commission will be your extracurricular activities and hobbies associated with the educational activities. For example, you want to enter the faculty of linguistics, you speak a foreign language at a decent level and help others to study it by organizing free courses.

Universities require a letter of motivation not only to learn about the performance and awards of the applicant, but also so that the applicants themselves really think carefully about why they generally take such a serious step in life as entering a university, and whether they truly desire this.

The average size of a motivation letter is 300 words, but for some applicants three dozen are enough to declare themselves. One such example is an essay by a student named Nigel, who said that he had written a three-sentence statement of purpose to get into Stanford:

"I want to teach English at the university level. To do this, I need a PhD. That is why I am applying."

That was the whole thing. It definitely portrays Nigel as brash, risk-taking, no-nonsense, and even arrogant person. If this is how you want to portray yourself, then by all means do this. But you should also know that Nigel's statement of purpose is an all-or-nothing proposition. You can bet there will be members of probably any admissions committee who will find Nigel's statement of purpose offensive, even disrespectful. And they might not want such a student at their school, although there still remains a chance to get the approval of one of the professors.

Try to make your paper-and-ink self come alive. Don't just say, "I used to work on an assembly line in a television factory, and one day I decided that I had to get out of there, so I went to college to save my own life." How about this: "One Thursday, I had soldered the 112th green wire on the same place on the 112th TV remote, and I realized the solder fumes were rotting my brain. I decided college would be my salvation." Both 35 words, but the latter is more likely to keep the admissions committee reading.

If there are controversial moments in your academic past, tell about them so as not to lose the trust of the admissions committee. For example, in one of the semesters you had only Cs. In this case, it is worth writing a short paragraph about what caused this (emotional problems, life difficulties), then demonstrate how skillfully you were able to deal with this, and now your average score is quite high. Presenting such a situation under a favourable angle, you will make an impression of a determined person, able to face challenging situations and overcome difficulties in a timely manner.

If you have already managed to work somewhere or took an internship, be sure to indicate this in a motivation letter. Pay particular attention to the details of employment that are directly related to the chosen profession. Consider how you can relate the work done and experience gained to the acceptance criteria.

Members of the selection committee are interested in your strengths: talents, skills, sports achievements, victories in school or university competitions, participation in scholarship programs and more. It’s not at all necessary that the achievements are too significant; it’s enough to tell in a motivational essay what you recall with pride and warmth in your heart, for example, you successfully passed exams at a music school, participated in various clubs (drawing, sports, dancing, etc.), or did volunteer and charity work. It is important to describe those moments that speak of you as a talented, versatile, and interesting person. At the same time, members of the selection committee are interested not in a dry list of skills and achievements (for this there is a CV, or resume), but your ability to reflect and draw conclusions from the experience gained.

To get away from a simple enumeration of skills, we recommend using the ABC method[3]. Its essence is to describe each skill, answering three questions:

| Element | Question | Example |

| A — Activity | What have I done? | I am the school captain of the football team. |

| B — Benefit | What skills have I gained? | This shows I have good communication and teamwork skills. |

| C — Course | How will this prepare me for the course? | This is relevant to business studies as being able to communicate effectively is an important skill when working on group projects. |

The above example is quite simple and aims to show how to provide evidence to each skill you mention in an understandable way.

To begin with, describe the reason you chose this university. Then name one or two professors and what exactly attracts you to their program. Such an approach will introduce you as a person who "did his homework", who is so interested in the chosen direction that he laid the groundwork.

You do not just need to write their names, since anyone who uses the Internet (which is almost everyone) can do this. Mention something that will show respect for the work done by professors. Moreover, it is not necessary to choose the most famous of them, since it is likely that other potential students will do the same. It is better to opt for a lesser-known professor who really seems interesting to you.

"The best essays that I've read are from people who've said they’ve learned a lot about themselves through this application process." — Sally O.Jaeger, Director of Admissions, The Amos Tuck Business School, Dartmouth College.

Before sending the final version, be sure to take the time to analyze the resulting essay: you should carefully review its contents, pay attention to the presentation style, the presence of grammatical and lexical errors. Usually even the obvious errors cannot be seen on the first or second reading, so ask a friend or senior colleague to check the motivation letter. Or just let it rest for a couple of days and then read it again to understand what needs to be fixed.

Yes, we already said that it is worth getting an opinion from the outside, but this time you are asking questions not about yourself, but about what you got as a result. Ask professors or teachers about the format and style of writing that is most appropriate in a particular case. Along with the text, be sure to indicate the initial requirements that were presented to the letter of motivation.

Similar to the preparatory stage, complete this list with specific questions for each case. Maybe you have doubts about representing events correctly, or whether you translated the names specific to your university accurately.

Adjust the essay, taking into account the advice received. But do not think that this is where your work on the letter ends. An epiphany may strike you even after sending an essay to a university. This might end up being crucial information so it is wise to write it down in case you want to submit documents again for later deadlines.

In order to spark the interest in the admissions committee, you should avoid the most common mistakes made by applicants.

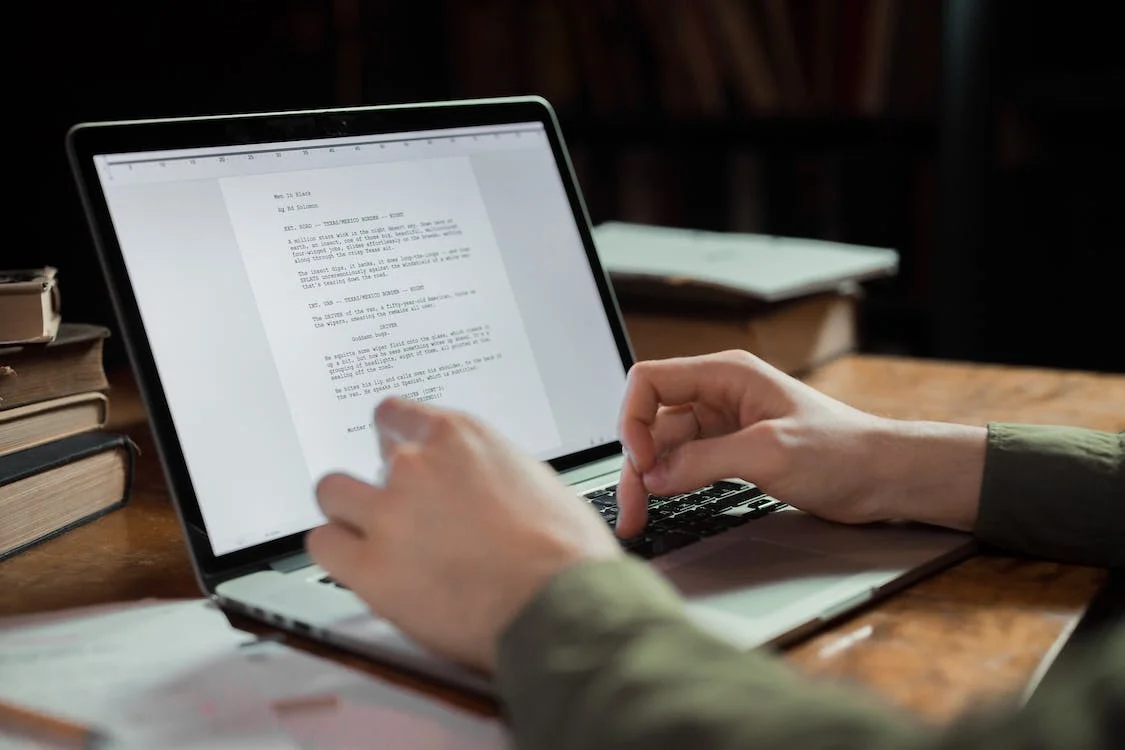

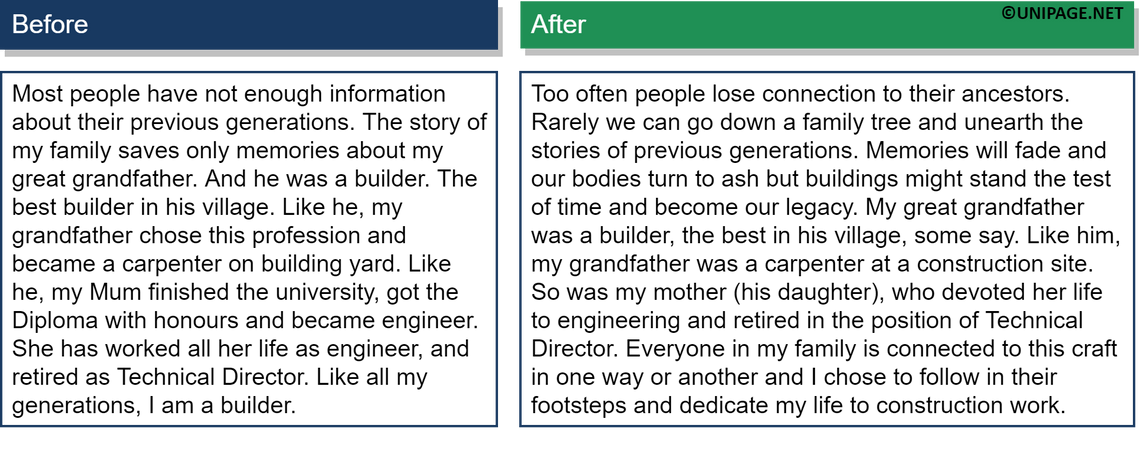

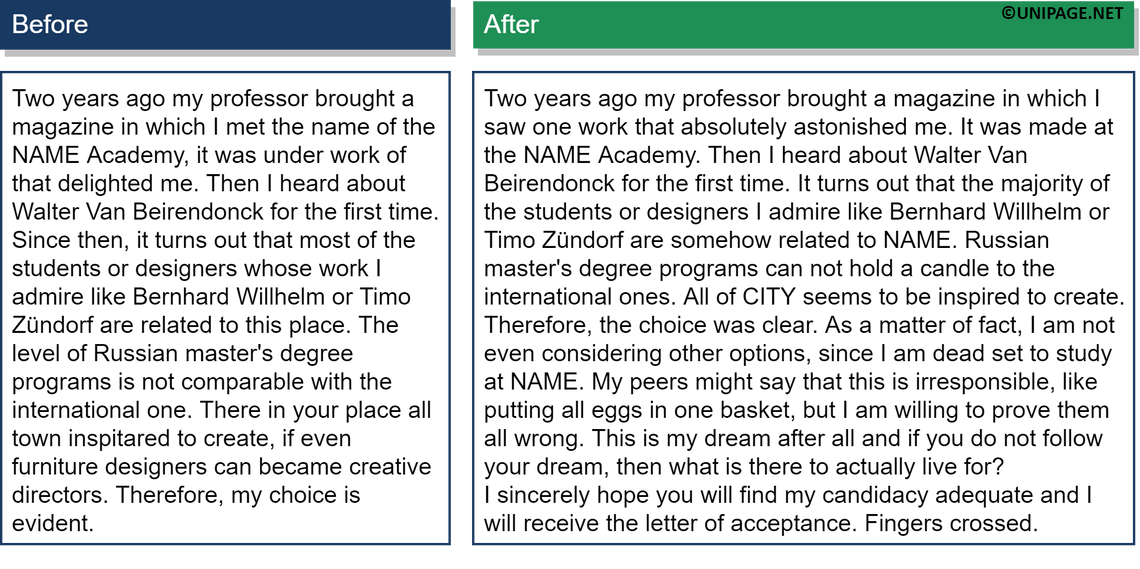

We have collected several interesting excerpts from the motivation letters of real students in two versions: the original and edited by UniPage specialists.

* Spelling and punctuation of the authors are preserved in their original form.

Pretty good "hook" in the introduction part of the letter. Here we can see a story of a third-generation builder. In the original excerpt we can sense the idea of craft inheritance, but it is not explicitly expressed with words. After editing the motivation of the student goes beyond the desire to preserve the family craft, and transforms into the idea of leaving the legacy in the form of a building, that will keep the memories of its creators. This might seem a little too sublime, but it shows the author's personal stake in the profession, that now has a subtle sheen of valor and nobility.

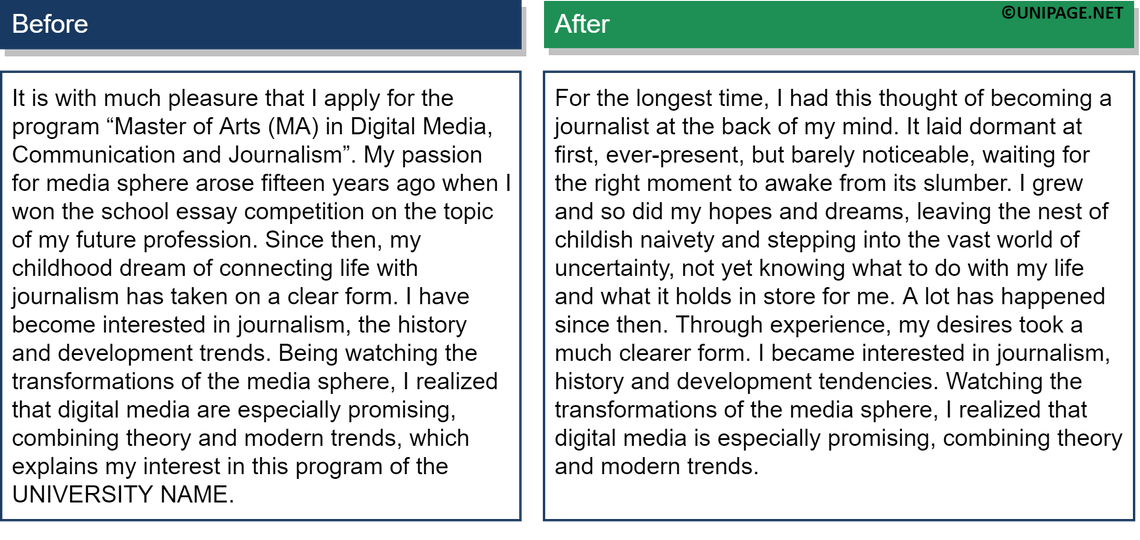

An excerpt from the letter of an experienced journalist, who already works, but strives for more. The body of the letter was fine but the introduction part felt incredibly dry. For example the essay competition "hook" could have been way more fun, it certainly has potential, but as is, the whole introduction is unacceptable for a journalism program applicant. In editing we fixed some of the stylistic issues and made it more sophisticated. There’s not much factual information, but it sets the benchmark for the applicant’s literary talents. The core theme is of uncertainty about the future and gradual realization — the calling was always close.

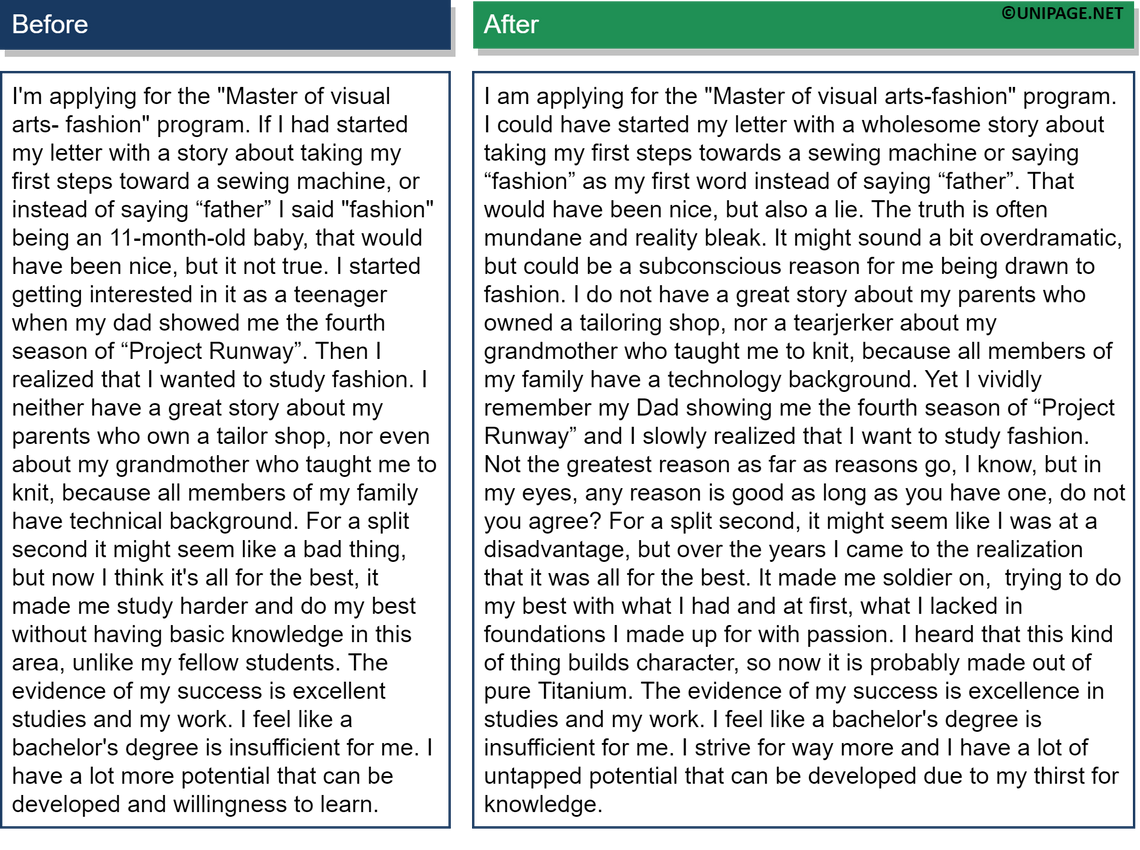

A very original and lively letter. The irony of the situation is that the author (a girl) has nothing interesting to say, unlike her peers that often come up with "special" reasons and situations. This is the case when a lack of an interesting story turns out to be a really engaging one. In this context a simple desire to learn and realize your potential sounds sincere and immediately makes the reader empathise with the author. After editing this thought reached a conclusion: no matter how mundane your reason is, it is a good one, since a lot of people don’t have any reason at all. A rhetorical question helps to create an illusion of an actual conversation, and in turn bridges the gap between the author and the admission committee, helping them to know the person behind the letter a bit better.

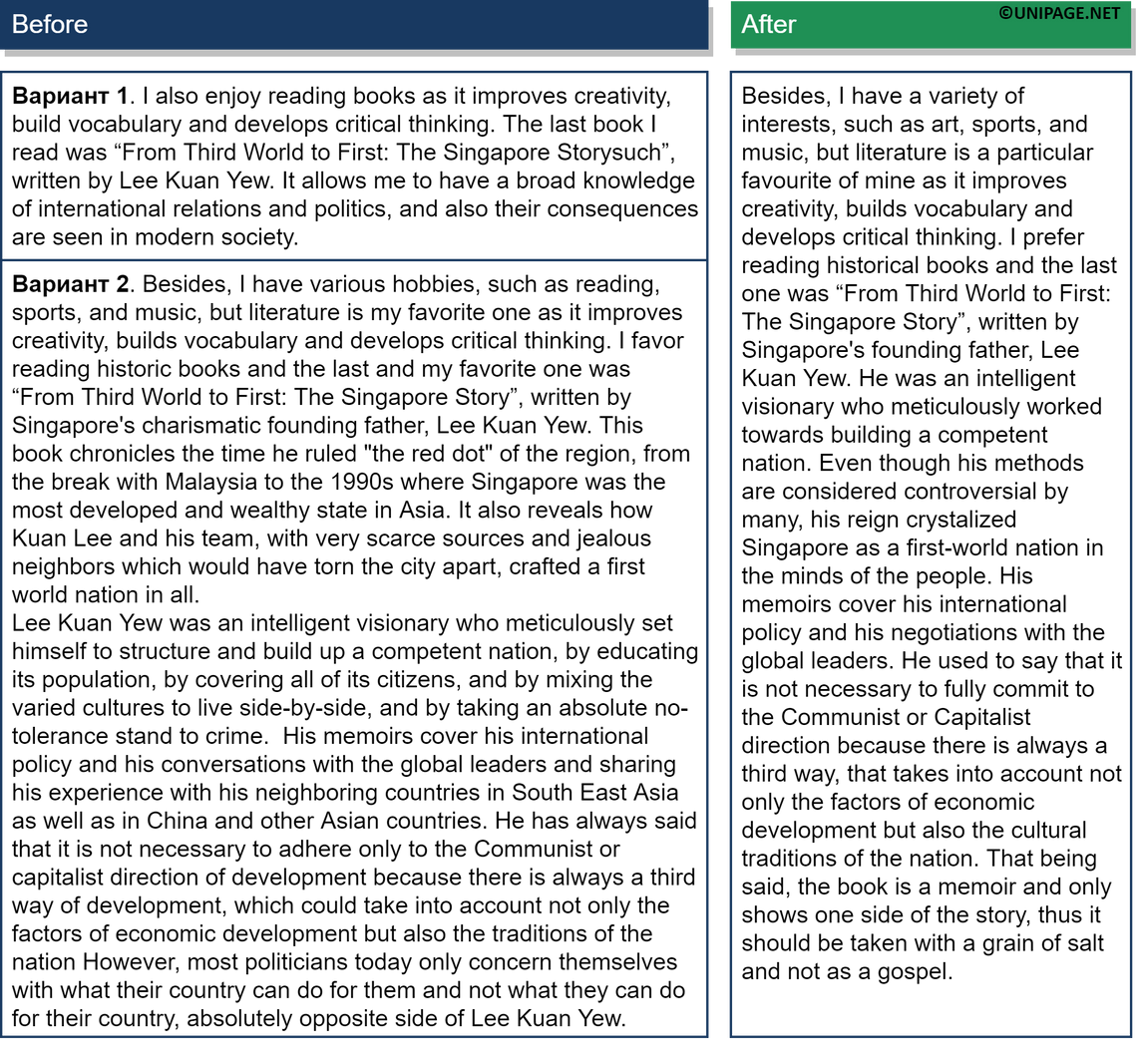

In version 1, you can write the title of literally any book and the meaning of the paragraph won’t change. It is very inconsequential and says nothing about the author's personality. Variant 2 has that personal touch, but has its own issues. For context: the author is applying to a certain prestigious university and wants to study politics and international relations. Being diplomatic is crucial. However not only the author gives a pretty binary representation of Singapore’s first prime minister, but also uses offensive language. For example saying "jealous neighbors" might be considered an insult towards SEA countries. In the last sentence, without mentioning any particular politician, the author manages to insult the whole professional group, which might lead the admission committee to question the applicant's diplomacy skills. In the editing we softened the edges while trying to preserve the authors position, taking other perspectives into account. It is important to understand that we cannot predict the personalities of the people responsible for the admission of applicants, we don’t know whether they sympathize with this politician or not. In general this advice is applicable to the majority of programs, you should remain sincere, speak your mind, but not paint the world as black or white.

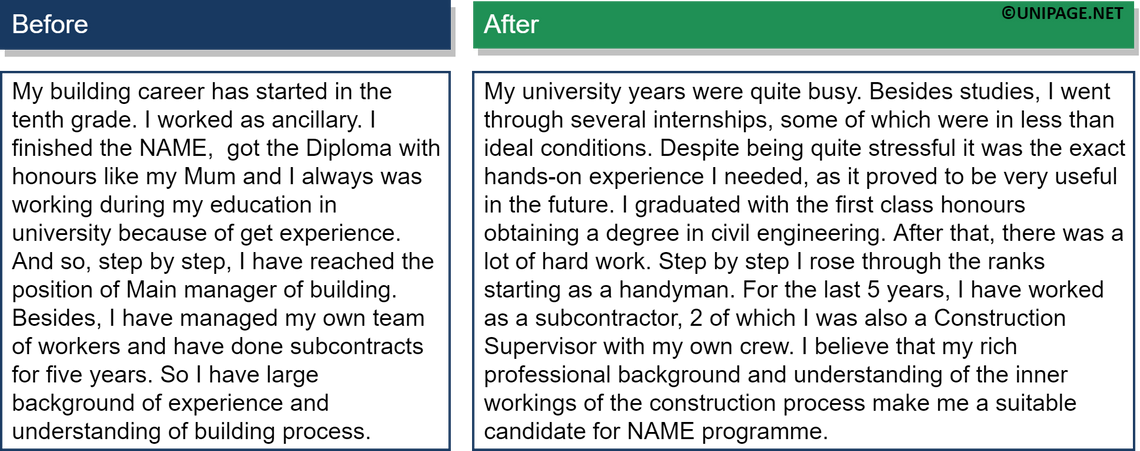

Originally the author speaks about his work experience, which in itself is very important, but due to the dry listing of facts it doesn’t make a desired impression. No doubt, there’s a lot of hard work behind all these achievements and speaking about it (without boasting of course) might show the applicant’s determination. Very often the admission committee is interested not so much in the end result, but in the journey the applicant took and his ability to overcome obstacles.

This excerpt from the conclusion is remarkable due to the fact that the author mentions people whose work inspires her. Thanks to this her choice of the academy sounds justified and thought out. During editing we added some all-or-nothing attitude (the student was interested only in this university) and wishful thinking along with some creative decisions like rhetorical questions and casual style. Please note that this approach might work for creative specialties (fashion in this example), but in other fields might be considered insulting and frivolous.

In addition to general recommendations that apply to almost any motivation letter, it is necessary to take into account the specifics of a future specialty. We tried to collect tips for you in several areas of preparation. This section, of course, does not provide comprehensive recommendations, but can be a source of inspiration and ideas[5].

The article covers only the general principles of writing a motivation letter. In order to account for all the subtleties, you can seek professional help from UniPage. Based on the many years of experience, we will edit your motivation letter: we will cover your strengths and add depth to your essay, check grammar, improve the presentation style, help you to avoid generic writing and make your application truly memorable. You can find examples of our work in the "Analysis of motivational letters" section. Moreover, not only we can improve your motivation letter, but also take upon ourselves the handling of a full package of application documents, thereby saving you from the unnecessary paperwork hassle.

60+ countries

we work with

$1,000,000 saved

by students through scholarships

6,400 offers

our students got